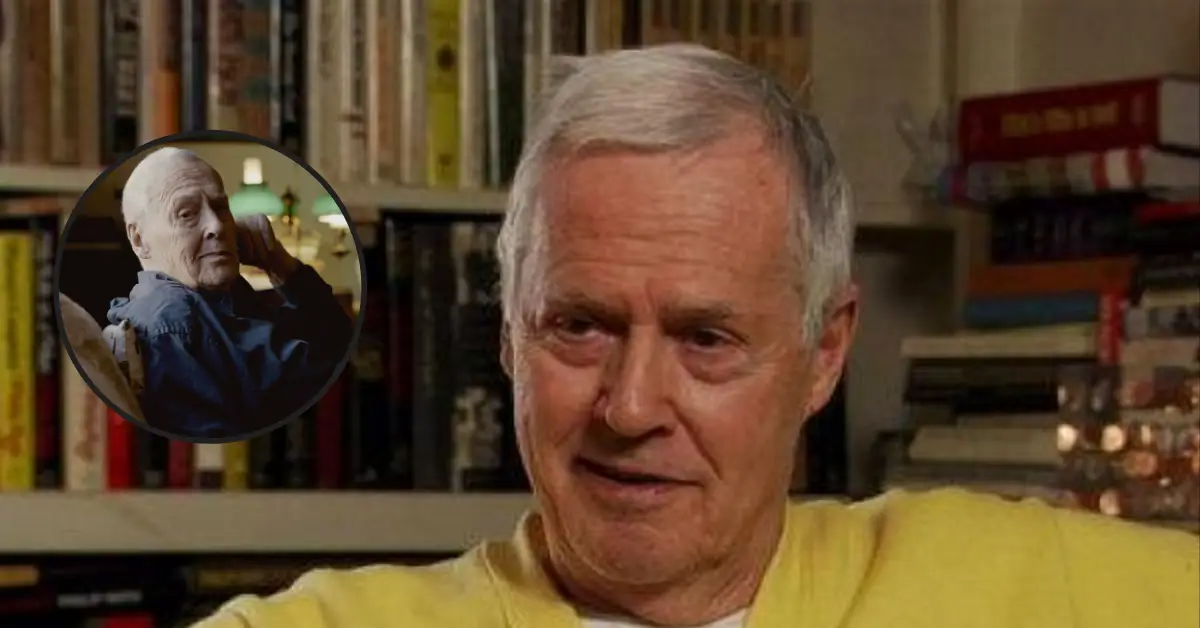

Composer Ned Rorem Passes Away at Age 99: Composer Ned Rorem passed away Friday at his Manhattan Upper West Side home. He was known for writing entrancing music and posting candid diaries about his life and relationships. He was 99.

A niece, Mary Marshall, confirmed the passing but did not provide a cause.

For a guy who had said, “To become famous, I would sign any document,” Mr. Rorem’s 1976 Pulitzer Prize for music was both an exhilarating moment and, as is customary, an opportunity for sarcasm. He claimed that the Pulitzer was “the decree that resentment is now unseemly.” And at least you pass away officially if you pass away in humiliation and filth.

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra’s “Air Music” piece, commissioned for the American bicentennial, won the award. The New York Philharmonic gave the world premiere of Mr. Rorem’s Symphony No. 3 in 1959, among many other orchestral compositions. However, his vocal pieces remain his most enduring appeal.

Related post:

- Betty White Died Six Days After Suffering A Stroke!

- John Aniston Passed Away: The ‘Days of Our Lives’ Star Has Died At The Age of 89!

He was hailed as the greatest art-song composer of his time by Robert Shaw, a leading choral leader in America. And it seemed to last forever.

When his masterpiece “Evidence of Things Not Seen” was first presented in 1998, Mr. Rorem was 74. It was hailed by New York magazine reviewer Peter G. Davis as “one of the musically richest, most delicately fashioned, most voice-friendly collections of songs” by an American composer. It is an evening-long song cycle for four singers and a piano that incorporates 36 poems by 24 authors.

Avant-garde theories and their proponents, including contemporary masters like Pierre Boulez and Elliott Carter, had no appeal to Mr. Rorem. In response, several critics believed him to be a miniaturist incapable of supporting more extended compositions, lacking in innovative ideas and vitality. Harold C. Schonberg of The New York Times noted in his review of “Miss Julie,” the Rorem opera based on Strindberg’s play when it was performed by New York City Opera in 1965, “His melodic ideas are completely bland, without in profile or distinctiveness.”

Image source: Newindianexpress

While the conservatism of Midwestern Quakers may have been represented in his works, Mr. Rorem’s personal life was, for many years, a marvel of excess. To put the matter to rest, one might only point to his estimate that he had slept with 3,000 guys before marriage. But contrary to what that assertion might imply, his writing on his experiences was much more self-aware, humorous, and depressing.

He encountered three significant American composers in a single weekend while he was an 18-year-old conservatory student: Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and Virgil Thomson, who later served as his mentor. One of the many columns he published for The Times, in this case on the occasion of Copland’s 85th birthday, was his reminiscence of the adventure. He usually started the story with himself, yet he eventually warmed to presenting the main character with elegance and affection:

“When I was a youngster attending the extremely formal Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, I occasionally traveled to New York to cause trouble. One weekend, before getting on the train, Shirley Gabis, a classmate, suggested that I stop in to see my old friend Lenny while I was up there (I had gone to see Virgil Thomson, whom I had never met, about working as his copyist).

Bernstein introduced me to Copland after telling me that “Aaron likes to know what young composers are up to”; as a result, I spent an afternoon humming my melodies for the well-known musician. Having accepted the position with Virgil, I immediately took an interest in Aaron and Lenny. For the following 42 years, despite many ups and downs, I have remained a steadfast friend of all three individuals. What a weekend!”

Except for two fruitful years spent in Morocco, Mr. Rorem moved to Paris in 1949 and remained there through the late 1950s. He won over the influential patron of the arts, Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles, and was soon accepted into her home and social circle.

The primary reason he continued to compose in France for so long was because of her, he said. “She has not only given three pianos but also funded performances, clothed, nourished, and housed me,” he said.

Within a short period, he met many famous and glitzy people of the time, including Picasso, Dal, and Man Ray; Jean Cocteau; the composers Francis Poulenc and Darius Milhaud; Alice B. Toklas; and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

RIP #NedRorem

The only man I have ever met to have dated the Vicomtesse de Noailles and Nöel Coward.

“The end of love is like the Boléro played backwards.” pic.twitter.com/GUYp7n6B9b

— Richard Coles (@RevRichardColes) November 19, 2022

Dropping names is one thing. It might become carpet-bombing with the gossipy Mr. Rorem. He wrote a series of confessional books, starting with “The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem,” adapted from his journals from 1951 to 1955 and published in 1966. These books mentioned hundreds of famous and unknown people while offering a pastiche of detailed accounts of his sex life, pieces of music criticism, and endearing anecdotes.

When he went to see Wanda Landowska, the grand dame of the harpsichord, in Paris one day to present her a concertino he had written, she immediately removed the pins from her hair, which was falling in waves to her waist. Take it, she commanded. “Pull it hard, take it in handfuls, and never let anyone know you’re wearing a wig!”

Eliot Fremont-Smith, writing a review of “The Paris Diary” for The Times, was struck by Mr. Rorem’s complexity as a self-described “coward” who dared to tell everything at a time when so many gay musicians and artists were secretive and as an outrageous narcissist who could still recognize his ridiculousness:

He wrote that I looked like a jar of honey with my canary-yellow blouse, my golden legs in khaki shorts, my tan sandals, and my orange hair. However, he said, “Famous last words of Ned Rorem, smashed by a vehicle, chewed up by the pox, stung by insects, in great pain: ‘How do I look?'”

The diary’s sensual passages may also be self-deprecating. While wandering through Europe in a state of wretched lovesickness for an Italian man, he made the following observation: “The choice of lover is one’s own business, but if you’re Beethoven in love with a hatcheck girl, or a hatcheck girl in love with Beethoven, or Tristan, or Juliet, or Aschenbach, or the soldier on furlough, the suffering is equally intense and its expression just as banal.”

Over the years, Mr. Rorem exposed numerous gay acquaintances and was aware of the repercussions. However, he told the somewhat bewildered interviewer for The Times in 1987 that “it never occurred to me anything you say about someone can be the incorrect thing to say.”

Despite his love involvements and binge drinking, he returned to the United States with his future in hand—a Guggenheim fellowship and the possibility of a string of commissions, foundation grants, and academic positions.

For the lyrics to his song back home, he began to resort to American poets more frequently. He used writings by Theodore Roethke, Donald Windham, Jack Larson, and Emily Dickinson, among others, in his 1963 song cycle “Poems of Love and the Rain.” Then came “War Scenes,” with lyrics by Walt Whitman, and dozens more songs and song cycles over the next forty years.

Is The Atlanta Symphony Made Its World Debut In 1985?

He created vast and little instrumental compositions, such as “String Symphony.” The Atlanta Symphony made its world debut in 1985, and in 1989, the orchestra’s recording of the piece earned a Grammy Award for finest orchestral recording.

Regarding his other career, Mr. Rorem followed the Paris journal in 1967 with a similarly open diary from New York. His marriage to organist and composer James Holmes, with whom he lived in a New York apartment and a property on Nantucket for 32 years until Mr. Holmes’s death in 1999, then improved his life.

More domestic than erotic, “The Nantucket Diary of Ned Rorem, 1973-85” was written. As usual, “Lies: A Diary, 1986–1999” was frank and humorous, but it also had a gloomy undercurrent about his partner’s impending death: “He is despondent. He seems to be a burden hanging around my neck. Is horrified by the medical bills’ rising costs. However, he is my life. What does money serve, then?

Although frequently overshadowed by the personal admissions of the diaries, critics generally concurred that Mr. Rorem’s writings about music—illuminating appraisals of Ravel, Stravinsky, Gershwin, or anyone he happened to be thinking about or listening to—represented some of his best work.

According to him, the Beatles’ best songs “compare with those by composers from great eras of the song: Monteverdi, Schumann, Poulenc,” thus he also enjoyed them. Then, using the “increasingly disjunct” arch of “Norwegian Wood,” he analyzed to demonstrate that “genius doesn’t lay in not being derivative, but in making good choices instead of poor ones.”

On October 23, 1923, in Richmond, Indiana, Ned Rorem was born. His father was a medical economist who taught at Earlham College in Richmond by Clarence Rufus Rorem, an Anglicized version of the Norwegian Rorhjem. Gladys Miller Rorem, his mother, was a Society of Friends member who participated in peace activities.

Ned had piano lessons from a teacher who introduced him to the works of Debussy and Ravel when he was still a little child after the family relocated to Chicago. It began his lifelong aversion to the French and their music.

After spending two years studying at Northwestern University’s music school, his official education was finished with a master’s degree from Juilliard in 1948. He then received a scholarship to attend the Curtis Institute. The following year, already fluent in French and eager to fall in love, he set off for Paris.

No one in the immediate family has survived.

Mr. Rorem was still going strong well into the twenty-first century, long after many of his modernist critics had become irrelevant. Supporters showed up at his concerts to help celebrate his 80th, 85th, 90th, and 95th birthdays; each time, the crowds grew older while he appeared to be unchanging.

In the months that followed the attacks of September 11, 2001, he worked on an ambitious 10-song cycle titled “Aftermath” as part of his ongoing pursuit of greatness. His chamber opera “Our Town,” which was based on the Thornton Wilder play and has a J.D. McClatchy libretto, had its world premiere in 2006 at the Indiana University Opera Theater. It was presented in 2013 at Denver’s Central City Opera, receiving positive reviews. It was first performed to positive reviews at the Juilliard Opera Center in 2008.

Throughout his lengthy career, Mr. Rorem penned hundreds of pages about the relationship between music and words, the need to respect the poet’s intent, and the singer’s desire to enjoy themselves while performing. But he claimed that the straightforward answer to why he wrote the song was, “Because I want to hear it.”

Leave a Reply